- Home

- Richard Kluger

Beethoven's Tenth Page 23

Beethoven's Tenth Read online

Page 23

“Maybe,” said Mitch. “But it all still makes me edgy.”

“You mean because there are no rough edges—and because your own forensics people couldn’t find any holes in everything they looked at—and now this alleged letter from the archduke also checks out so consistently, therefore the whole business must be contrived?”

“Not must be contrived—could be contrived—by shrewd and greatly knowing con artists.”

Clara shook her head. “Forgive me, Mitch—that’s perverted thinking, not just skepticism.”

“Possibly,” he conceded and let the subject hang for a moment. Then he resumed, “And there’s still the Rossini connection—that does bother me, the way I know it does you. We need to dig into that more and find a plausible answer before you’ll catch me doing any high-fives.”

“Right,” Clara conceded. “I’m working on it—and so is Mac.”

.

“…and then in my best judy holliday voice, I asked him the perfect twit question. ‘Harry,’ I said, ‘when you get right down to it, why does it matter who wrote this Beethoven thing? I mean, if it’s beautiful music, it’s beautiful music—regardless.’ You should have seen the look he gave me—as if I were radioactive dog poop. Honestly, when God was handing out senses of humor, he saved a corker for my sweet beau. He thinks sick jokes, pratfalls, and rectal thermometers are the height of hilarity.”

Lolly Cubbage on the telephone was scarcely more bearable than in person. Lately, as the Tell situation intensified, she would call every few days, seemingly without design but always pumping Clara for the latest news and sharing whatever she was privy to. Harry, she revealed, was growing more excited by the day over the possibility of a major killing when—“he hardly says ‘if’ anymore”—the manuscript was finally put up for auction.

“Then maybe you shouldn’t tease him about it’s not mattering who really wrote it,” Clara counseled, “or he’ll never take you seriously again.”

“The man needs to lighten up.”

“But selling the genuine article is what his business is all about.”

“Point taken,” Lolly conceded. “Actually, I think he’d be ecstatic if he only knew how well our little Lincoln Center project is coming along. Did I tell you Penny Gillespie might come in for fifty? Our pledge total is seven seventy-five already, and we’re just gearing up.”

“It’s not ‘our little project,’ Lolly—it’s yours. You know I’m very much on the fence—”

“I’ll bet you sing a different tune—no pun intended—once your lover boy gives the thing his official okay.”

“Don’t count on it. Anyway, I think you’d be tying Harry’s hands—or maybe get him charged with trying to rig the auction. That would kill C&W’s reputation.”

“Well, that’s the last thing I want to do, of course, but I’m afraid you’re overreacting, pumpkin. It’s not as if I’d be the one doing the buying as a private party—this would all be for the good of Lincoln Center. And who do you think Harry would rather see as the buyer—Lincoln Center or the Maharajah of South Punjab? Oh, and did I mention Penny’s bright idea? She says if we’re really serious about this thing, we need to form a consortium with a couple of other heavy hitters, like a recording studio or even one of the movie companies—and what a boffo film this would make. Penny’s got a first cousin wired in to Dreamworks who thinks the soundtrack CD might rake in even more than the regular recording of the whole symphony.”

Lolly’s high-powered excitement was apparently contagious. “That may make some sense,” Clara allowed, not to be a total wet blanket. “Otherwise, you’d need to raise a small army of big givers—which could get very difficult since nobody’s heard a note of Tell performed—and probably won’t before the auction.”

“Exactly what I was thinking,” Lolly agreed. “And I have the perfect solution in mind that would work to everybody’s interest.” Once Tell was deemed authentic, why not, she proposed, stage a private performance about two weeks before the auction—“by the philharmonic, of course, at Lincoln Center, of course, maybe in Alice Tully Hall”—of just the first movement as kind of an hors d’oeuvre, so potential bidders could get a real sense of the work? “No press, no critics—attendance by invitation only, which means Harry gets to control the list as he likes—except I’d insist on our being able to invite, say, a hundred or so of the biggest potential givers to our kitty. I’d have to convince Harry each of them would be a possible bidder at the auction, but I’ll bet the philharmonic would gladly perform it gratis, just as a historical thing—the very first time any orchestra will ever have played it—especially since the point of the event would be to give our Lincoln Center group the inside track to package a winning bid.”

“But that would give you an unfair advantage.”

“You’re not listening, sweetpea. I said other serious potential bidders would be invited as well. I just think we’ll be able to top them all if we put it together right.”

It was not entirely a crazy idea, Clara recognized, assuming that the music would in the end be judged worthy of public performance. Even the savviest people for the leading record labels, who would presumably be among the most active bidders for Tell, would first need to hear at least part of the work performed with the full tutti sound; trying to read the score of a complex, never-before-heard Beethoven orchestration in order to gauge its quality would be no easy trick. But dare she encourage Lolly? And shouldn’t she tell Mitch, perhaps right away, what Lolly was cooking up, so Harry could stifle it if the whole plan struck him as underhanded? Unless, of course, he chose not to. He just might subscribe to Lolly’s argument that nobody was being disadvantaged by her efforts on behalf of Lincoln Center. In fact, her strategy, if seen as no more than a little benign string-pulling behind the scenes, might even get Harry elected to the center’s board of trustees. The problem was, telling Mitch about Lolly’s ploy would only make him crazy; he’d know he ought to tell Harry about it but couldn’t without betraying Lolly’s confidences to Clara and possibly dealing a fatal blow to the Cubbages’ shaky marital relationship.

“Well,” Clara said as neutrally as possible, “it may be an idea worth considering.”

“Good girl! Why don’t you come help me pull it off—as soon as your involvement in it with Mitch is over? And frankly, I think you should also give up that whole tiresome grind to become a grubby academic and devote yourself instead to socially correct do-gooding—not to mention having a high old time of it.” Lolly paused half a beat, then added, “Also having a baby—possibly two. One will do, though—it did for us. Children can be such a bother—”

“Really? I hadn’t heard—”

Sarcasm was lost on Lolly Cubbage, mired in her alternate universe of privileged self-absorption. She must have glanced at her Rolex. “Oh, sorry, gotta fly—if I’m thirty seconds late, Dr. Latham makes me wait hours in the stirrups—the rat. But he’s cute and cracks such great jokes.”

.

“don’t worry about emil,” Rolfe Riker told Mitch over their dessert coffee at the Silver Birch Chalet, Salzburg’s best luncheon spot. “His bark’s a lot worse than his bite. I can’t say the same about that cur of his, though—watch out when he’s eyeing you. A very protective beast.”

Whether or not he succeeded in enlisting Emil Reinsdorf, the biggest catch of all to sit on C&W’s five-member panel of Beethoven experts chaired by Mac Quarles, Mitch was delighted to have snared Riker in his net. Just turned forty, Riker was among the foremost European musicologists of the emerging generation. His book, The Symphonic Evolution, on the development of the form from Haydn to Mahler, was considered most illuminating for its dissection of Beethoven’s revolutionary contributions to the genre. And he was a German as well, a native of Leipzig, though now a permanent resident of Austria and on the University of Salzburg faculty. “Unlikely as it seems,” said Riker, “I’m quite fond of Emil, for all

his crankiness. He can be quite engaging when he’s not putting you down.”

Mitch had allowed himself one month to assemble his panel while a trio of musicologists, selected by Quarles and working under tight surveillance in the top-floor apartment at C&W’s offices, was producing a cleaned-up transcription of the Tell manuscript, pending further scholarly study and revision. Once the legible transcription was in hand and spot-checked to be sure it accorded with the original messy rough draft, Mac’s Beethoven panel would be far better able to assess the composition. It had been agreed that five was the optimum number of participants for the panel of experts, including Quarles as the chair—enough viewpoints for genuine diversity but not so many as to invite wholesale dissension or encourage factions. Each of the four members besides Mac was to receive an honorarium of $50,000 plus expenses for two weeks of effort, the first week dedicated to examining the sketchbooks privately on C&W’s premises, the second to meeting with the other panelists to compare notes and try to thrash out a consensus as to the work’s authenticity. Unanimity was desirable, of course, but each panelist would be assured the right to file an independent opinion. Mac was to preside as a voting member and write the final report. He and Mitch, with Clara’s concurrence, had decided the proper balance would a German, an Austrian, two from other European countries, and Mac himself, the house American.

A German member, as predicted to C&W by the overbearing attaché from that nation’s Ministry of Culture, was proving the hardest to engage. Of the dozen names on the list of eminent German candidates whom Mac had carefully culled and Mitch had deferentially approached by letter and follow-up phone calls, ten declined to meet with him in view of the disapproving advisory issued by the German Cultural Ministry. “They’re a very obedient bunch,” Mitch reported to Harry, “and rigidly orthodox types, according to Mac.” Among the native Germans solicited, only Rolfe Riker, the most junior name on the list, and Emil Reinsdorf at the National Institute of Music (better known as the Berlin Conservatory), the hoariest of the Beethoven sages, had agreed to meet with Mitch.

He had begun his recruitment trip in London, where he and Clara put up at her parents’ house while he stalked his first panel candidate, the matronly Anna Wertham Hayes, who lived in Hampstead. Hayes, whose family had fled Austria shortly before the Anschlüss, was the author of Prometheus Unsilenced: The Life of Beethoven, reputed to be the best twentieth-century biography of the maestro. Now among the gray eminences at the Royal College of Music, she also served as co-editor of its Journal of Classical Music, without peer in its field.

“In the unlikely event this manuscript should prove to be authentic,” she groused when Mitch took her to lunch at the Dorchester, “I’ll have to revise the biography—a pleasure I’d just as soon forgo. So I may prove a singularly testy participant.” He assured her such resistance to bedazzlement would be entirely in keeping with the show-me spirit of the inquiry.

“In that case, count me in,” she said over her Cointreau-drenched flan. “It all sounds stimulating, the pay is generous—in fact, I’d do it for nothing just to see Emil Reinsdorf turn apoplectic every half hour. The man loathes me—but I’m in good company.”

Mitch’s next stop was in Denmark to see the gnarled but amiable Torben Mundt, one part gremlin, two parts Peter Pan, who divided his life between professorships at the University of Copenhagen and Lund University in southern Sweden. He was a good friend of Mac Quarles, who told Mitch that Torben’s hefty opus, The German Sound, was the most insightful piece of critical writing on music he had ever read, witness its translation into twenty-two languages and still counting. It was Torben’s judgment even more than Mac’s that the addition of the German pair of Emil Reinsdorf and Rolfe Riker would bring ideal strength and variety to the panel—“but you should understand that we’re all predisposed to find this Tell bonbon a pile of scheisse.”

“Just as we want it,” Mitch asserted and flew off to Salzburg.

Riker had no problem dismissing the German government’s attitude toward the Tell discovery and its possession by an American as “leftover Junker mentality—it’s one reason I’ve chosen not to pursue my career in Berlin. The conservatory is very much under the Culture Ministry’s thumb, and there are still too many around both places living in the past—the glory days of German music, not to mention military might.”

Mitch was not cheered by this report. “And Dr. Reinsdorf subscribes to that as well?”

“Not in so many words, of course—and not when he’s among foreigners, certainly. The joke among younger people in the field is that Emil is more Germanic than Siegfried—he’s hopelessly territorial when it comes to others poaching on German musical expertise. I’ve heard him describe Anna Hayes’s Beethoven biography as ‘seven hundred pages of adolescent panting’—and he calls her ‘La Blimp.’ He can get quite nastily ad hominem when he wants to.”

“Are you saying that he’ll try to dictate to our panel? And do we need that?”

“‘Try to dictate,’ yes—and yes, you need him, especially if you’re hoping to persuade the world that you’ve got the real goods in your hands. If he says otherwise, it will certainly make the rest of us hesitate, no matter that he’s usually on a one-way ego trip.”

“How can I persuade him not to snub us?” Mitch asked.

“You’re already halfway there,” Riker supposed, “or he wouldn’t have agreed to meet with you. He’s got no worlds left to conquer within his field, you see, so he doesn’t have to worry about offending the people in power.”

Ten years earlier, it had been different, Riker confided; Reinsdorf had assiduously positioned himself to become elected director of the Berlin Conservatory, the pinnacle of German music academia, yet for all his medals and scheming, he was passed over. The position reopened five years later, but the board of governors wanted a younger man for the taxing job. “Give Emil credit, though—instead of turning into a bitter old man, he jokes about how lucky he was not to have become sucked into all that administrative quicksand—and he’s still productive and full of interesting ideas. Get some wine into him, and he’ll give you an earful on Beethoven’s secret sexuality.” Riker grabbed the check before Mitch could. “Treat Emil like a hero—make him feel it’s his patriotic duty to keep your panel honest.”

.

while mitch remained in Europe, recruiting the Beethoven authorities Mac Quarles had selected to make up C&W’s elite authentication panel, Clara had returned to New York to attend to new duties assigned her at Lincoln Center and to keep an appointment with her Columbia faculty adviser on the status of her doctoral thesis.

Her supervisors at the city’s great performing arts complex had rewarded her élan and diligence by promoting her to a team of fundraisers assigned solely to seek contributions to the Lincoln Center endowment from current patrons and longtime season subscribers. The process, involving luncheons at superior—but not the priciest—restaurants, appointments at the homes of promising prospects, and meetings with donors’ attorneys and financial advisers, would entail politesse, patience—and a high threshold for frustration, Clara was told while being assured there was no higher calling among the center’s volunteer staff. Her reward was increased from a pair to a set of four superior house seats at any combination of twenty-five performances, whether by the philharmonic, the Met, or the theatrical company at the Vivian Beaumot.

On top of this satisfying news, her Columbia dissertation adviser, Associate Professor Mark Aurelio, was now coming around, Clara was happy to learn, to her proposed change of topic from Schubert’s symphonic work, his Ninth in particular, to the unfolding saga of the Tell Symphony. Although the professor recognized that Clara could bring an inside vantage point to recounting the story of the discovery of the work and the investigation to authenticate it, he was concerned lest the thesis turn into journalism, something more appropriate to appear in The New Yorker or Harper’s, especially if the manuscript tur

ned out to be bogus. Clara was forced to tell Aurelio that she was unfortunately constrained from disclosing to him any of the findings of the C&W inquiry thus far, but he seemed satisfied by her latest report that the effort was making good headway and its prospects were “promising but by no means certain” in this still-early phase of the process. She agreed to keep pursuing the Schubert study even while the drama over Beethoven’s alleged Tenth Symphony was being played out and to advise Professor Aurelio of the outcome as soon as she was able—“If we leave your topic hanging indefinitely, the faculty doctoral committee will be on my back. Neither of us needs that.” She understood his veiled reference to the departmental vote to be taken that spring on his tenure status.

The next day, Clara decided to take a midmorning break from her academic reading and note-taking at home and go for a jog in Riverside Park along the narrow greenway beside the Hudson. In good weather, she and Mitch would make the run side by side two or three times a week before breakfast—between Seventy-Second and Ninety-Sixth Streets, up and down twice for a total of about four miles. Other days, when Mitch was at work and her Lincoln Center schedule freed her up, she would bike over to the park at Eighty-Sixth and jog three times around the reservoir, where the going was slower because there were many more runners and walkers but she felt safer because of the company.

With Mitch away, she had cut out the early-morning run along the river—jogging alone amid the sparse turnout of exercisers at that hour made her uneasy. Now and then, though, due to Mitch’s or her own scheduling problems, she’d go out solo to Riverside Park at ten when there were more people around and, well, it was right next to their apartment house. On this morning, the last in September, it was perfect jogging weather, just over sixty with moderate humidity and a light breeze off the river, and she was relishing the easy rhythm of her fit body in motion over the broad pedestrian promenade. Her iPod was playing Elgar’s Enigma Variations, and her heart was beginning to pine for her absent lover, due home after a weekend stay with her parents at their Cotswolds cottage. Her wandering mind refused to settle on any of the clamoring strands that wended through it.

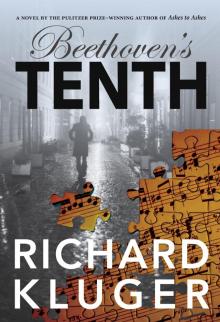

Beethoven's Tenth

Beethoven's Tenth