- Home

- Richard Kluger

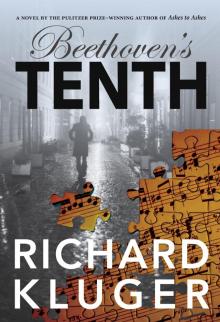

Beethoven's Tenth

Beethoven's Tenth Read online

ALSO BY RICHARD KLUGER

Fiction

When the Bough Breaks

National Anthem

Members of the Tribe

Star Witness

Un-American Activities

The Sheriff of Nottingham

With Phyllis Kluger

Good Goods

Royal Poinciana

Nonfiction

Simple Justice

The Paper

Ashes to Ashes

Seizing Destiny

The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek

This is a Genuine Vireo Book

A Genuine Vireo Book

A Vireo Book | Rare Bird Books

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90013

rarebirdbooks.com

Beethoven’s Tenth

Copyright © 2018 by Richard Kluger

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever, including but not limited to print, audio, and electronic. For more information, address:

A Vireo Book | Rare Bird Books Subsidiary Rights Department,

453 South Spring Street, Suite 302, Los Angeles, CA 90013.

Set in Dante

epub isbn: 9781947856875

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data

Names: Kluger, Richard, author.

Title: Beethoven’s Tenth a Novel / Richard Kluger.

Description: A Genuine Vireo Book | New York, NY;

Los Angeles, CA: Rare Bird Books, 2018.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781945572982

Subjects: LCSH Beethoven, Ludwig van, 1770–1827—Fiction. | Zurich (Switzerland)—Fiction. | Composers—Switzerland—Zurich—Fiction. | Zurich (Switzerland)—History—Fiction. | Historical fiction. | Mystery and detective stories. | BISAC FICTION / Historical | FICTION / Mystery

Classification: LCC PS3561.L78 B44 2018 | DDC 813.54—dc23

For my witty, irrepressible nephew Bruce,

gifted wordsmith and faithful supporter.

“Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on…”

—John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn”

“He left thirty-two piano sonatas and nine symphonies,

yet the more intimately they are known, the less can one even

hazard a guess as to what the thirty-third sonata or the tenth

symphony would be like. They would be Beethoven, and that is but

the statement of a formal enigma. How many movements they would

have…whether the theme would be slight and the handling sublime,

whether there would be an orgy of rhythm or a feast of melody or

both, whether they would follow an old form or invent a new one:

all these are matters of which nothing intelligible can be said…”

—George Dyson, The New Music

“…His emotions at their highest flight were almost godlike;

he gave music a sort of Alpine grandeur.”

—H. L. Mencken on Beethoven

Contents

Overture

{1}

{2}

{3}

{4}

{5}

{6}

{7}

{8}

{9}

{10}

{11}

{12}

{13}

{14}

{15}

{16}

{17}

{18}

Coda

Author’s Note

Overture

Vienna, 22 April 1814

Dearest father, dearest mother,

There is such excitement here as I have not felt before, you see it everywhere on the people’s faces & hear it in their voices, all due to the news that has just reached the capital that Paris has fallen to the allied armies & Bonaparte is at last a captive. The very skies exult! Every bar of music in the air sounds a glorious anthem. And to crown my exhilaration, whom do you think I should encounter last night when a few friends and I went to celebrate at the Zum Schwan, our favorite haunt but much too dear for threadbare music students like us to frequent except on rare occasions? None other than the maestro himself! And at the very next table!

I had arrived at the tavern early & took a table in the back to sip a beer & await my friends when I spied him, in his great coat and wide-brim felt hat, taking choppy little steps & claiming the large table next to mine. He threw off his hat and coat, revealing a none too tidy blouse with a hole at the right elbow. Shaking off the server & saying he would wait for the arrival of his companion, the maestro spread open his copy of the Wiener Zeitung to catch up on the momentous news—which gave me a fine chance to study him without seeming rude.

Sad to say, but the supreme genius of the music world does not cut a striking figure. He is short, wide, bow-legged, and almost homely by the usual standards of male beauty. His face is dark and pocked, the eyes deep-set fiery coals, the nose broad & flat as an African’s, the front teeth jutting so as to cause his lips to thrust. Yet his brow is magnificent, very full and round, a titan’s head made larger still by the superb hair, so wonderfully abundant & admirably unruly, like some male Medusa’s, and when he runs his hand through it, the coarse & bristly locks go comically in all directions. His hairiness extends even to the backs of his hands, & his fingers, I saw, are wide, almost splayed at the tips—not a shape at all suitable for sublime mastery of the piano, such as he once commanded.

I was struck most of all by his uncongenial, indeed nearly repellent expression. Not quite a scowl, but very little hint of merriment within. And no wonder, considering the pathetic spectacle his hardness of hearing has reduced him to of late. My friend Berthold attended a concert at the Augarten a short time ago at which the maestro was to conduct his own compositions. Uncertain of the orchestra’s sound & tempo, he tried to compensate by sheer physicality, sinking on his knees during the soft passages & almost disappearing behind the conductor’s platform like a dwarf, then leaping up like a giant by way of signaling the forte passages, his hands & arms beating with a frenzy. This gymnastic exhibition did not entirely distract the musicians at first, but soon the maestro began to run ahead of the orchestra & reverse his pattern, which totally unhinged the musicians & left the kapellmeister no choice but to relieve the maestro of his wand & force him from the stage. The scene was equally sorrowful when I myself attended a concert at which his keyboard play lacked all clarity & precision. They say he will perform no longer.

How gravely his deepening deafness is troubling the maestro I learned with the arrival shortly of his dinner partner, a man perhaps a dozen years his senior & rather better attired. His friend sat close by him and spoke into his left ear. They were not exactly shouting at each other, but I could overhear their every word. His companion asked if he had read all the war news, & the maestro said he guessed the emperor would sleep better that night, adding, “not that I care much—”

“So they’ve treed your hero—glory be,” said his friend.

“No hero of mine since the day he crowned himself,” said the maestro. “Anyway, I’m off politics for good.”

“Then why are they doing your ‘Battle’ Symphony five times next week, Ludwig?”

“It’s not politics, Nikolaus,” said the maestro, “it’s money. That’s what they want to hear when their armies win—and I didn’t arrange it.” As a pleasantry, Nikolaus asked whether the watch he had sent him as a gift was keeping good time, & the maestro replied,

“How should I know? I can tell tempo, but the time of day eludes me.” Nikolaus smiled and then asked the outcome of the maestro’s appointment with a certain physician. “Ah, Dr. Weissenbach, you mean.” The maestro shook his head. “Do I dare trust a surgeon from Salzburg?”

Nikolaus looked reproachful. “I know, maestro—you’re sure they’re all quacks with their charlatan cures of almond oil and herbs and ear drops and cold baths—”

The maestro shrugged. “At least this Dr. Weissenbach isn’t prescribing miracle pills. He says the deafness has nothing to do with my belly and bowel problems—and all those halfwits who told me so have no understanding of anatomy.” His affliction, the Salzburg doctor told him, is likely the result of nerve damage from an infection—the ringing & buzzing that he hears prove it. Nikolaus wondered what sort of infection could be the cause, and the maestro cast his fierce gaze heavenward. He had once contracted a bad case of typhus, & Weissenbach suspects that’s what planted the evil seed that has eaten away at his auditory nerve for years now. His friend asked if the Salzburg healer held out even faint hope that the process could be reversed.

“He fears it’s degenerative and unstoppable. In a few years I’ll hear no music whatsoever—or anything else.”

Nikolaus grasped his friend on the upper arm. “Weissenbach is not the last word, you know. There are other healers—and Salzburg, as you say, is not the medical capital of the world.”

“Quite so. Weissenbach himself said as much. He wrote out the names of some healers of the deaf he knows of, if I’m willing to travel. I told him of my possible trip to England, and he said there was someone of high repute in Edinburgh—another in Amsterdam and a third in Zurich.”

That mention of dear old Züri nearly made me jump. How I wished to turn openly to them and say, “Zurich is my home city—and the maestro’s music is greatly beloved there. I am here to study the violin and would be immensely honored to be of help, maestro, to cure your terrible malady. Please tell me the name of the Zurich physician you were given, and I shall write my parents at once to inquire discreetly in your behalf. Pray, let me!” But of course I dared not be so forward.

Soon my own friends came, gay revelers like the rest of Vienna just now, and I could eavesdrop no longer. When I thought again to look over at the next table, it was empty. Only then did I recount to the fellows with me what I had overheard, & Berthold said he thought the maestro’s woes could be solved if he would just get his hair cut instead of letting it overgrow his ears. I think it was a cruel joke. It is a great misfortune for anyone to become deaf, but how should a superb musician endure it without giving way to despair?

I hope the both of you are well and cherishing the spring. How I shall miss the sight of the chestnut trees in bloom at the lakeside and along our lovely Limmat. There is nothing half so delightful in this beautiful city, not even the pastries that the locals adore. Please give dear Katherine a hug for me.

Your loving & devoted son, Kurt

{1}

The blinking light on Mitchell Emery’s office phone signaled that he had a voice-mail message—two of them, as it turned out. The first was from his wife Clara.

“Oh, hello, mister—sorry I missed you.” The tone was pleasingly low with a barely perceptible edge of wryness. “Forgot to mention before you left that I’m on for lunch with Lolly today—my treat, no less. She’s had me out three times, so I owe her—and she is your lord and master’s wife, so I’ll have to put on my best imitation of good behavior.” Clara’s good breeding and continental education indelibly shaped her speech, even the most casual remark. “Anyway, I won’t have room left for our usual gourmet dinner, so if you don’t mind, I’ll pick up some cold cuts, and we can have a sandwich or something else light. Feel free to pig out at lunch, though I know you’re heroically abstemious on workdays. Anyway, hope all’s well at your shop and—um—still love you like crazy, big guy. Bye.”

Mitch smiled inside. Her calling him “big guy” had become a long-standing gag between them because in her flats she was a half inch taller than he was—and she was careful not to wear heels except when they had a dress-up occasion. Not that he minded her height; on the contrary. He had thought her statuesque from the first moment he saw her, and it only added to her appeal. Of course, if he had been on the shrimpy side himself instead of six feet even, it might have been a different story. Physically and emotionally, they were well matched—two highly independent people who had elected to blend their contrasting backgrounds and temperaments.

Mitch’s other voice-mail message was more urgent. “Something a bit out of the ordinary has come up,” said his caller. “Drop by whenever the mood suits you. Sooner would be better.”

The voice was reedy, its cadence deliberate yet fluid, with every syllable equally uninflected, and the speaker’s message typically terse and cryptic. Its imperative tone was nonetheless unmistakable. Since he owned the place, Harry never bothered to identify himself when phoning subordinates. In fairness, though, his superior air seemed neither put on nor a character flaw; to Mitch it was simply natural that anyone named Harrison Ellsworth Cubbage III would sound, act, and be like that, considering that he owned a Harvard PhD in fine arts and half of Cubbage & Wakeham, the New York- and London-based firm that had been in the connoisseurship business for six generations.

C&W, as the auction gallery was known in art and big-money circles, owed much of its sterling hallmark to the expertise of its Department of Authentication and Appraisal. This crack unit, now under Mitch’s supervision, included nine full-time curators: three in the paintings and sculpture office and one each in manuscripts and documents, jewelry, ceramics and other collectibles, relics and artifacts, arms and armaments, and textiles. Every curator, moreover, was authorized, whenever it was deemed necessary, to draw upon a far-flung network of specialists in the academic, museum, and commercial worlds, so that no bidder at a C&W auction ever had to fear purchasing something less than advertised. Only the genuine article reached the house’s auction block. True, there had been rare exceptions over C&W’s 137 years in business, but in each case the full purchase price was repaid promptly along with interest, abject apologies, and the proprietors’ redfaced discomfort. The erring authenticator was dismissed summarily; there could be no margin for mistakes in such a high-stakes game.

“Sorry, just heard your summons,” Mitch said, appearing in the open doorway of the co-owner’s office at the other end of the second-floor hall. “Something interesting come up?”

“Everything that comes up here is interesting,” Harry said in mild rebuke. “I thought you knew that by now, Mitchell.” From the first, his boss had insisted on calling him Mitchell, saying he thought nicknames were undignified—except his own. Harry was big on dignity.

Mitch gave a slight nod. “I misspoke—sir.”

“I wanted to give you a heads-up on the meeting you’re booked to join us for this afternoon at three,” Harry said. “Chap from the wilds of New Jersey is coming in with his lawyer—Gordy has spoken with him and recommends that we give them a hearing. They’re bringing us a manuscript of something called the William Tell Symphony—well, it’s in German, as I understand it—the title page, that is.”

Mitch shrugged. “Is the title supposed to mean something special to me?”

“Probably not. But according to the lawyer, his client found the manuscript at the bottom of an attic trunk while cleaning out his late grandfather’s house in Zurich a few weeks ago.”

“I see. Well, yes—that would follow—William Tell—Switzerland. Probably a patriotic pastiche, and pretty dreadful.”

“I wouldn’t be surprised,” said Harry, twiddling an unsharpened pencil of the kind he occasionally chewed on as a pacifier, “but possibly it’s a bit more than that. Would you care to hazard a guess at the name of the composer on the title page?”

“Swiss composers are not really my thing, to be honest. In f

act, I don’t think I can name a single one.”

“Me neither, to be equally honest. But the listed composer definitely wasn’t Swiss.” Harry savored being in charge of any exchange, especially with an underling.

“All right,” said Mitch. “I’ll play your silly game. How about Duke Ellington?”

Harry snorted. “You might have tried Rossini, since he did the—”

“Rossini didn’t write symphonies, so far as I know—only operas.”

“The Jersey lawyer told Gordy that this symphony has singing parts.”

“That,” said Mitch, “would probably qualify it as an opera.”

“Nevertheless, the composer apparently called it a symphony—and he should know.”

“And why is that?”

“Because,” said Harry, “the name on the title page is Ludwig fucking van Beethoven.”

Harry was allowed to say “fucking” whenever he chose as a kind of droit de seigneur, even if everyone understood it wasn’t entirely dignified for him to do so.

A small, quick intake of breath betrayed Mitch’s momentary loss of nonchalance. “Well, him I’ve heard of.”

“Good man.”

“Hold on. Didn’t Sotheby’s auction another Beethoven manuscript a little while ago—it supposedly just popped up in an old filing cabinet at a Philadelphia seminary or someplace? The story got a lot of print and airtime, as I remember.”

“Not to mention a couple of million bucks for the finder,” Harry confirmed. “And that wasn’t even a new composition—I checked it out online right after the call came in from New Jersey yesterday. The manuscript was Beethoven’s attempt to adapt his Grosse Fuge for the piano—which is pretty small potatoes compared to a purported whole, spanking-new symphony by the all-time world champion of that musical form.”

Mitch wondered if Harry was pulling his leg as a kind of playful test of his gullibility. “What if that recent episode inspired a copycat or two to start digging around the old homestead for an inexplicably abandoned Beethoven manuscript? Or maybe this New Jersey gentleman will also be bringing us—for good measure—Saul of Tarsus’s left sandal, found by a passerby after a sandstorm near the northern end of the Sea of Galilee—”

Beethoven's Tenth

Beethoven's Tenth